“Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player | That struts and frets his hour upon the stage | And then is heard no more.” These immortal words of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth open Stevan Riley’s 2015 BAFTA-nominated documentary Listen to Me Marlon, an exploration of previously unheard audio from Brando’s personal recordings. We hear these words, in Brando’s voice, coming from Brando’s face, but not as we’ve previously known it: a digital reconstruction of the middle-aged star, then 11 years in the grave, is animated with uncanny precision to match his distinctive voice. Resurrected by virtual technology, Brando the method actor becomes Brando the virtual actor. His appearance from beyond the grave led me to recall Dustin Hoffman’s famous quip: “once you’re a star you’re dead already. You’re embalmed.”

Also known as ‘synthespians’, ‘silicentric’ actors and ‘vactors’, virtual actors are animated likenesses of human beings that play characters in a narrative (instead of flesh and bone actors). In most cases, virtual actors are computer-generated, digital clones of real people, rather than totally fictional creations with no real-life model.

The animated short Rendez-vous in Montreal (1987) is generally considered to be the first use of virtual actors. The film follows a romantic meeting between Marilyn Monroe and Humphrey Bogart: not recorded footage of an illicit affair, but an imaginative use of computer-generated likenesses of the stars to fantasise about a screen partnership that never was. To the contemporary viewer, the robotic and cartoonish animations pale in comparison to the capabilities of 21st-century animators; however, the figures are undoubtedly recognisable, raising questions about virtual actors and their human counterparts that are becoming more relevant as technology develops.

Pure animation is not the only way to create a virtual actor: in a Frankenstein-esque mode, previously recorded footage can be chopped and changed for new purposes. There are several significant examples of archived footage of famous faces being reconstituted for further use, such as the resurrection of Nancy Marchand as Livia in The Sopranos (old footage of Marchand’s face was stitched awkwardly onto a body double). Laurence Olivier’s appearance in Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004) as the holographic Dr Totenkopf was achieved by manipulating old footage and audio of Olivier, a progressive feat of digital reproduction that was in keeping with the synthesis of physical actors and CGI backdrops that the film has retrospectively become famous for.

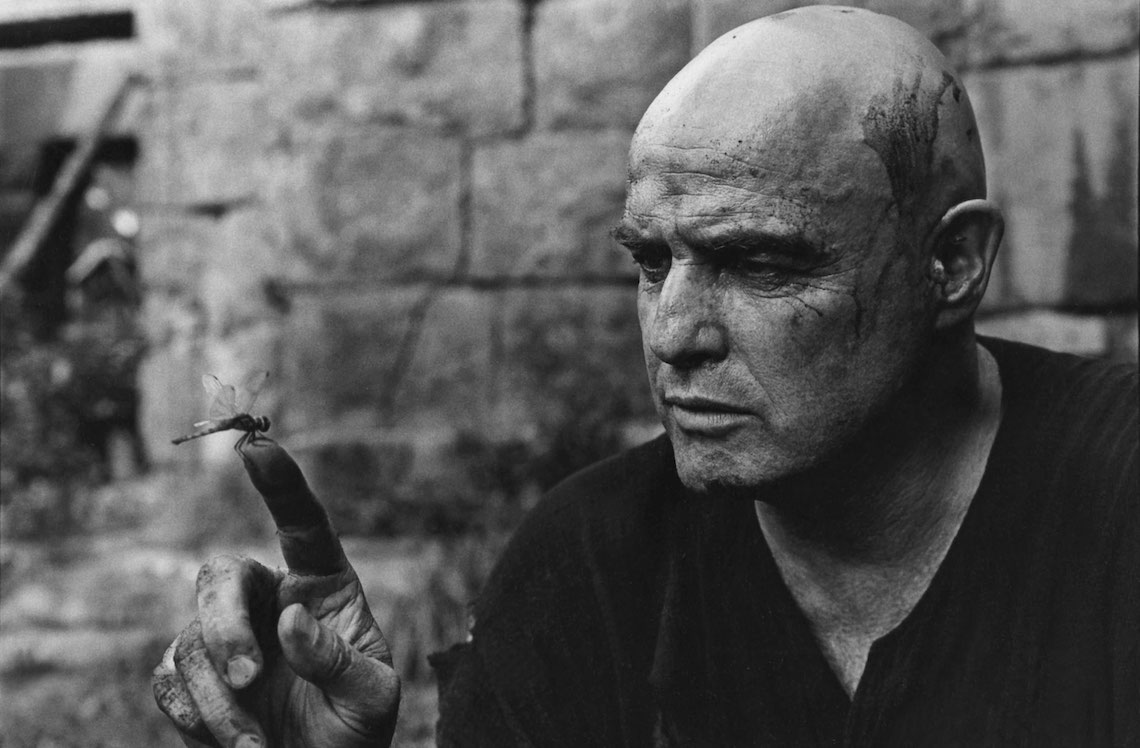

A similar example is Marlon Brando’s reprised role as Jor-El in Superman Returns (2006): rather than using his digital clone, previously unused footage from Superman (1978) was manipulated by animation technology to match separate archived audio to create the illusion of authentic footage of Brando. The Rhythm & Hues making-of clip is eerie in its exposition of the animated Brando as little more than an empty mask. However, despite the Frankenstein-esque composition of the part animated Brando, it also preserves as much as possible of Brando’s performance, prioritising the emotion in his eyes and retaining much of the human quality of the footage. Jor-El’s message from beyond the grave, particularly his assumption that “you don’t remember me”, is augmented by the context of Brando’s own demise and iconic presence on screen. At the beginning of Listen to Me Marlon, we hear Brando’s speculations on the future of acting: he suggests that “actors are going to be inside a computer”, and that rapid development of virtual acting will be the “swansong” for actors as we know them. The implementation of Brando’s image in new digital contexts ensures that his face will never be forgotten.

A more recent example of virtual acting is the appearance of Audrey Hepburn in Galaxy’s 2014 chauffeur advert. The digital reincarnation of Hepburn, created by British visual effects company Framestore (responsible for the CGI on countless ambitious projects, including Gravity (2013) and Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2016)) is so lifelike, it is hard to believe that it isn’t authentic footage. As Mike McGee explained in a Guardian article about the ad, they duplicated Hepburn’s face using 100% computer graphics despite the dangers of being unable to represent “crucial human subtleties” in a realistic manner.

Though the sophistication of these visual effects is undoubtedly applaudable, and opens up a wide range of exciting possibilities for creative filmmaking, it also unearths a plethora of problems. Virtual actors risk falling into the ‘uncanny valley’, a concept, first identified by robotics professor Masahiro Mori, which suggests that human replicas that are almost, but not exactly, like real people inspire feelings of repulsion. Monroe and Bogart in Rendez-vous in Montreal are not realistic enough to elicit discomfort, but the Rhythm & Hues clip of Marlon Brando’s disembodied face, with the slightly rubbery quality of the manipulated features, is thoroughly disquieting. However, Framestore’s Audrey Hepburn is too lifelike to inspire uncanny discomfort, suggesting that the forefront of visual effects technology has already surpassed this issue.

The replication of real people as virtual actors calls into question the limits of personality rights, particularly when the reproduced image is that of a deceased actor. Fred Astaire’s widow contested the use of his image in a Dirt Devil vacuum advertisement, prompting the controversial 1999 ‘Astaire Bill’, which protected dead actors’ images from being commercially exploited. Additionally, as Brando suggested, the existence of increasingly sophisticated virtual actors endangers the future of acting itself. These issues are explored in Michael Crichton’s 1981 thriller Looker, in which a number of models undergo a full body scan and are digitally reproduced for use in advertising.

Perhaps there is something inherently appealing about knowing that the public personality also has a private life. When quizzed about the marital status of his cartoon creations Mickey and Minnie Mouse in 1933, Walt Disney settled the debate by declaring that they were, in fact, married “in private life”, though often played unmarried sweethearts if required by the story. Could this be the future of gossip magazines: editors creating stories about the private lives of artificial public personalities? Funny, that doesn’t sound too farfetched.

Perhaps the capabilities of real actors will be reduced to but a “walking shadow” in the face of their digital counterparts. In relying so heavily on the weight of iconic images, we run the risk of creating and augmenting urban mythological figures who (almost) literally live forever. Virtual actors skirt the boundary between creative license, exploitation and stagnation. A metamodern twist on a postmodern problem.

‘Virtual Acting’ is an article written by Lana Crowe. You can find more from Lana on her site.