Few filmmakers embodied so fully an innate understanding of human perspective like Edward Yang. With unsparing perspicacity, Yang’s small yet extraordinary body of work shrewdly observed figures navigating the fraught expanse of globalization, a paradigmatic shift Yang and his generation witnessed in their native Taiwan after decades of brutal repression under the ruling party. This transition was not a painless one, and it is the paradoxical melding of social anguish with a rigorously controlled formalism that has earned him belated acclaim over a decade after his tragic death at the age of 59. Rediscovering his films like, 1986’s Terrorizers, provides a historical snapshot of the Taiwan Economic Miracle whilst reverberating in the present with discordant unease. Brimming beneath the cool veneer of the cultural conformity shaping Yang’s vision of Taipei stirs a primal scream waiting to be unleashed.

That discontent, which Yang identified in an interview with the New Left Review as “the typical phenomenon [of] outward conformity and inner rage”, was not specific to him alone. It had been broiling in a country which had witnessed nearly forty years of martial law under the Kuomintang (KMT) Party of Chiang Kai-shek, the former president of China forced into exile by Mao Zedong’s Communist Revolution in 1949. By the 1980s, the United States had symbolically recognized the People’s Republic of China as the official government of the region by closing their embassies in Taiwan, thus effectively quashing the KMT’s hopes of regaining the mainland. The ensuing disenchantment from the populace found a perfect analogue in a fledgling film industry which had coasted off what filmmaker Li Hsing called “selective realism”, or sentimental nationalist paeans to the agrarian sector, for years. After a marked decrease in ticket sales in the 1970s, the state-sponsored Central Motion Picture Corporation (CMPC) was desperate for new talent. With an audience who was, in Yang’s words, “thoroughly disillusioned with [the KMT’s] propaganda, and now much more confident in confronting it,” doors were opening for Yang and his fellow filmmakers, including Hou Hsiao-hsien and Wu Nien-jen, to make their dramatic entrance on the world stage.

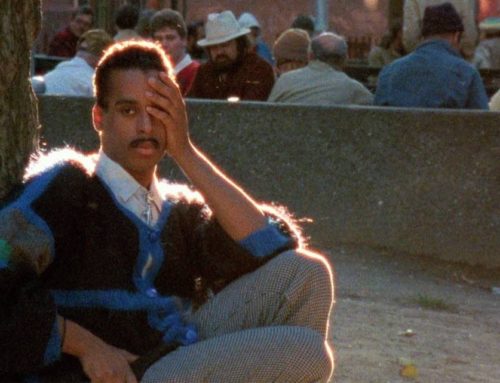

While his first two films displayed Yang’s influence of modernist European auteurs like Werner Herzog and Michelangelo Antonioni, Terrorizers proved to be Yang’s most reflexive film to date, a brooding, postmodern rumination on the liminal boundary between fact and fiction. The film tracks three couples whose paths intersect due to, among other things, a prank call that implicates one of the characters in an extramarital affair. That character, a career-minded doctor named Li Lizhong (Lee Li-chung), finds his already strained marriage to his wife Zhou Yufen (Cora Miao), a writer struggling to complete her novel, rapidly disintegrating. The prank caller, a Eurasian woman referred to in the subtitles as “White Chick” (Wang An), has her likeness captured by an amateur photographer (Ma Shao-chun) as she flees a derelict apartment building during an early morning police raid. He lives in an apartment with his girlfriend (Huang Chia-ching) while the White Chick turns tricks as she waits for her beau (Yu An-shun) to be released from prison. That both photographer and subject remain linked speaks to a power dynamic favoring the former due to the financial boon of a bourgeois family. Yet the latter ultimately upends that dynamic in disarming fashion.

The relationship between subject and photographic apparatus is one which draws inescapable comparisons with Antonioni’s Blow Up. Like Antonioni, Yang’s camera chronicles a historical snapshot of urban living while casting doubt over the authoritative veracity promised by the photographic image. Take a series of three successive shots early in the film; we see a dead body lying in the street before cutting to a row of buildings imbricated in overlapping, geometric patterns, a woman hanging laundry on her balcony; then back down to seemingly the same street with the body now gone and a hoodlum taking flight. With this simple progression, Yang subtly instills a degree of uncertainty in our temporal and spatial orientation to the narrative, entrusting his audience to regard discrete shots like the pieces of different puzzles.

Another disquieting effect lies in recurring shots of characters looking directly into the camera. The first instance, when the photographer is directed by the police officer (Ku Pao-ming) leading the raid, establishes a syntactic relationship between the shots, each of which assumes a particular character’s perspective. But Yang subverts his own visual syntax later when Yufen tells Li, in an extended monologue, the depths of her resentment toward him for their failed marriage. She initially addresses him across the table, matching the eyeline from his complementary shot. But as she continues speaking, her gaze flits toward and fixates on the camera, snapping accusatory sentiments like, “you still don’t get it!” By speaking both within and beyond the filmic reality of her suffocating sphere of domesticity, Yufen doesn’t break the fourth wall as much as slyly align the audience with her husband, who meekly confesses later to a colleague he hasn’t read any of his wife’s work.

If this Brechtian device implicates the audience within the film’s image of social malaise, it does so with a psychological ferocity that is more evocative of Nicholas Ray than Michelangelo Antonioni. If Yang’s 1991 magnum opus, A Brighter Summer Day, can be considered his Rebel Without a Cause, then I’d argue Terrorizers is his reconfiguration of Ray’s 1956 masterwork Bigger than Life, which used a sensationalist news story about prescription drug abuse to probe the brutality lurking beneath the surface of suburban conformity. When Ed (James Mason), the patriarch of that film, confesses to his wife (Barbara Gordon) the belief that they are, in fact, boring people, it is a sentiment which finds its echo in Yufeng’s own wounded cry to us and her husband that “all you know are ordinary routines.” What Ray saw in the Nuclear Family, Yang refracts and amplifies for a growing Taiwanese urban middle-class.

Yet, like so many of Yang’s masterpieces, Terrorizers transcends mere polemic by possessing a canny prescience of things to come. The dissemination of digital media is alluded to in shots of Yufen’s television interview following her novel’s success projected on several screens. More striking is a moment of a gentle breeze lifting the separate pictures in the photographer’s collage portrait of the White Chick, causing them to resemble quadrangular pixels in a digital image. Considering Yang worked extensively in computer programming before becoming a director, this visual resemblance could not have been entirely coincidental. In any case, the trappings of a post-analog world Yang’s film portend can be felt beyond Taiwan. In an obituary penned for Film Comment, Olivier Assayas argued Yang’s legacy was most evident in South Korea, a nation which also emerged from decades of military dictatorship to produce its own generation of iconoclastic filmmakers. Like the New Taiwan Cinema’s audience, South Korea comprised of what Assayas called “a public attuned to a contemporary cinema that bears witness to its age while maintaining a passionate and figurative relationship with it…“ Indeed, it’s not difficult tracing Lee Chang-dong’s Burning, itself a bristling portrait of festering rage under a late-stage capitalist schema where truth and fiction intertwine, back to Terrorizers.

That Terrorizers could serve as a timely diagnosis of a post-historical, mechanized global economy only reinforces the film’s unnerving power. In his introduction to New Chinese Cinema: Forms, Identities, Politics, Nick Browne argued that Yang’s “historical perspective on this social world is a thoroughly synchronic one – the past is absent and the present strongly marked by the signifiers of the contemporary, imported world.” Indeed, what remnants of the past do remain manifest in pop culture staples, like the record of “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” the White Chick’s mother plays that subtly evokes the girl’s absent American G.I. father. But the past has a way of bleeding into the present, something Yang reifies by cutting from nocturnal reminiscence to wounded outburst as the photographer’s girlfriend, gripped by jealousy, tears down pictures of the White Chick hanging in his apartment. The tremulous serenading by the Platters provides the sole aural accompaniment to the visual obfuscation of curtains and darkness that conceal the expressions of the photographer and White Chick, respectively.

It is this attenuated connection to history, to culture, and to those whom we profess to cherish above all else, which informs the wounded heart of Yang’s masterpiece. The film’s timbre of longing curdles into bitter resentment and, ultimately, tragic violence. Yet what lingers longest is not the violence telegraphed in Yufen’s novel and realized by Li in the film’s climax, violence which may exist solely in a dream. What stays with us is the psychic unease wrought by the cyclical devastation ensured by a capitalist nightmare, one which we are feverishly struggling to awake from. If we do wake, like Yufen in the film’s closing moments, to a “new beginning”, it may be to a seemingly obsolete hegemony’s hierarchical structure remaining intact. In 2020, what could be more terrifying than that?

‘Understanding the Nightmare in Edward Yang’s Terrorizers’ is an article written by Nick Kouhi. You can find more writing and information about Nick on his Website.