What actually sets the masala movie blockbuster apart from the critically acclaimed indie sleeper? Is this the current state of the Indian Film Industry, or is there a chance of a blur?

Bollywood, also known as Hindi Cinema, has always been penned as the Indian equivalent to Hollywood. It is one of the largest film industries across the world, along with Hollywood, Nigeria, and China. It has become a global enterprise. Though, Hindi is not the only language spoken in the country, in fact there are 22 official languages in India and at least half produce their own films and now have fully-fledged industries outside of Bollywood. There are Tamil films, Telugu films, Punjabi films, Marathi films and many others, but Hindi films are considered the primary source of big screen entertainment. These kinds of films are considered India’s Independent Cinema. But language is not the only classification for independent films, as there is a whole sub-section in Hindi cinema that is not considered Bollywood, and why is that?

Bollywood is determined by these words; masala, blockbuster, super hit and the 100 crore club. What is the common denominator? Revenue. A very important, required factor for most producers and directors of the industry. And the style or genre of films that are made from these big budgeted/huge profit productions – action, comedy, family dramas. The content sometimes doesn’t even need to be spectacular; if it is helmed by some of Bollywood’s big names then they have large revenues in the bag from the offset. Another common denominator? Nepotism. It is one thing Independent films do not require, or do not depend on in their industry; all they need is a solid story, characterisation, and cast and crew talent. The rest, as they say, is history.

Ajay Bahl says the ‘Indian Indie is a reaction to Bollywood’ and ‘thrives on its non-confirmation of that style.’ Thus began the frequently spoken words; Bollywood versus Independent Indian Cinema. And after many years of festival recognition and new-found commercial appreciation, since its resurgence in the late 1990s, Indian Indie’s are set to overtake Bollywood, as discussed by Dora Ash Sakula for Raindance.Org. They are putting India on the map and the new crop of Bollywood actors is splitting their career paths between high grossers and critical acclaimers.

For instance Alia Bhatt was launched with the huge Dharma production Student of the Year and followed it up with a completely different cinematic angle in Highway and continued to do so with Udta Punjab and Dear Zindagi. But does her star power as a bigwig director’s daughter and Karan Johar’s protégé change the face of these Indie’s, or are they doing that all on their own? Whether it is the former or the latter, the question is still out there. Will they still be Indie’s? Will the word Independent and all its attached values cease to exist? Thus begins the momentous time in India’s film industry, the fine line between Bollywood and Independent Indian Cinema.

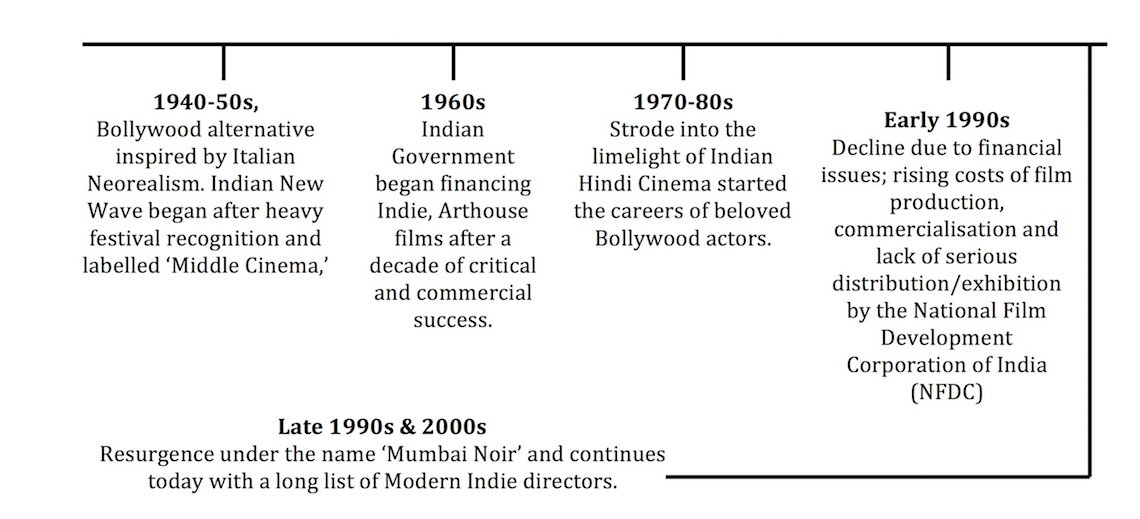

So lets discuss Independent Cinema in India, otherwise called Parallel Cinema, Indian New Wave and Mumbai Noir. How and when did it come about? The timeline below tells us the basics as:

The first Independent film to come out of India was in 1946, named Neecha Nagar – a story about the social realism of the rich and poor divide. As one of the Grand Prize winners for Best Film at the very first Cannes Film Festival, it paved the way for many more ‘Parallel Cinema’ style productions, like Uski Roti and Duvidha. Yet as you can see above, it didn’t last long. After a successful run of fifty years in the game, this cinematic movement failed to last due to the government’s lack of, well to put it bluntly, care. With no opposing factors in the mix, mainstream cinema took centre-stage and the Indian film industry became enveloped by love triangles, saas-bahu (mother-in-law/daughter-in-law) dramas and the unexplainable double-role action man. Now an independent movie may well include these normative stories and characterisations but the difference lies in the methodology.

Soumya Kalapa defines an Indian Independent film as ‘circumventing traditional Bollywood formula of song, dance and fanfare’ in favour of the ‘filmmakers personal and artistic vision.’ So on one hand, Bollywood gives us an ensemble slapstick comedy film like Housefull with an array of comical jokes, senseless mix-ups and a pointless song about not waking up the dad character. And then the other hand gives us Sulemani Keeda, an indie slacker comedy that is free-wheeling and open-hearted in its social and cultural message about ambition and friendship, as described by Pulp Fiction co-writer Roger Avary. The stark contrast of these two films brings to light the big question linked to keeping the line going between Bollywood and Indian Indies – which one would the audiences go to see in the multiplex? And there we go back to that age-old factor of revenue, the film that sells the most tickets makes the most money and is left in the minds of its audiences for years to come, which is why they have made two more of this calibre; Housefull 2 and Housefull 3. Same comedy, same cinemagoers, more money being raked in. Is that good cinema, meaningful in its message, or amusing for the 2 hours when you see it?

Bollywood tends to base its stories around a specific collective, or group, like two lovers, warring families or comical bromances and whatever happens as consequence of their actions becomes the story. An Indie will feature it in the background to be experienced as an escapist route from the significant subject matter at hand – like the social, political and cultural themes that are ignored and shoved under the rug. For instance, inter-caste/race/religion love, pre-marital relations, sexuality, crime and corruption are all examples of what Independent Cinema touches upon without hesitation, and what Bollywood runs away from in favour of the light-hearted entertainment. And why would the government stop backing these kinds of films? Because they showed the nation in a different light? A light everyone knows about, but is never overtly shown to the public in fear of international disgrace? That is a discussion for another day, for another type of writing, but the world of Indian Indie’s does do this…they surpass the boundaries of film production Bollywood has laid out on the table for them. And with that, they forge their own audiences, reactions and movements.

We can look at the examples of Bollywood film 2 States and Indian Indie Masaan. 2 States shows sex before marriage as a casual, fun, non-blasphemous deed as a fragment of a modern love story, representing Indian society and culture as accepting of these 21st century values. Although, Masaan presents the opposite message as it opens with the pivotal character being shamed for doing the same thing, and her sexual partner ultimately committing suicide instead of facing the music. Out of the two, which would you look at as a real depiction of sex before marriage? One would hope the former, but if it were the case, would indie filmmakers feel the need to write a story in such a way, depicting the latter? These questions and answers are up in the air no matter how progressive a society, country or world is, hence why that fine line still exists between these two areas of filmmaking. The methods used by Bollywood and Indian Independents to create the same story will always be different, that’s how you know which one is which. But is that on its way to a substantial decline?

Rituparna Chatterjee talks about a term yet to be officially coined referring to the consequences of this supposed decline. She means to say there is neither a mainstream cinema, nor an independent one; there is only a middle ground. With films like Udta Punjab, Kahaani and Piku, the classification that the words independent and arthouse pose is slowly losing their vigour. Why is that? The big bad words revenue and nepotism, but there is another and that is star power. Udta Punjab grazed the boundary line of the 100 crore club, grossing 99.67 crores, featured a stellar cast – three out of four are children of the Bollywood fraternity, and co-produced by Balaji Motion Pictures, one of the biggest production companies in India, founded by yet another family of the famed Kapoor name. That is what makes it Bollywood. But, what makes it independent? The content. The story rooted in a controversial topic that almost didn’t make it to the screens as it was filmed. The various censor board issues is one aspect of independent filmmaking that exemplifies the tectonic changes of the industry, as argued by Chatterjee. And Anupama Chopra declares that the content and subject matter is what makes an independent film; it is the defining factor that separates it from the masala movie fandom Bollywood builds itself upon. So the only way we can differentiate Bollywood and Indian Indies is within our own opinions. It is, and will continue to be, an on-going debate, a fine line discerning the two sectors. But with this makeshift conclusion, can the two co-exist or will they eventually blur into one style of filmmaking in the years to come?

Have a think.

‘The Fine Line between Bollywood and Independent Indian Cinema’ is written by Parveen Bhambra. You can read more articles on her blog shegoestothemovies.