Ghost In the Shell began life in 1989, created by writer/illustrator Masamune Shirow as a series of manga comics which followed the counter-cyberterrorist organisation Section 9 in a futuristic neo-Japan. The popularity of this initial series developed into a medium spanning franchise, with television shows, video games, action figures, novels and apps, furthering Shirow’s imaginings across platforms into popular culture. Director Mamoru Oshii brought the manga series to the cinema in both Ghost in the Shell (1995), now oft cited as a classic of the genre, and its sequel Ghost in the Shell: Innocence (2004) laying a groundwork of influence for a strain of contemporary Western cinematic science fiction. These cybernetic inflections and aesthetic dressage mutations were most notably appropriated in the Wachowski’s reality bending The Matrix, directly cited by the directors as an influence on their series. The buzz surrounding the upcoming live action version comes in large from the high benchmark the original feature set for both science fiction and animation but also because it appears to have captured the look and feel of the Ghost in the Shell series. And despite the trailer’s use of a toe curling cover of ’Break the Silence’ and the initial murmurs of Scarlet Johansson’s facial features being ‘asianified’ with CGI, this first full live action interpretation has so far generated a wave of positive excitement. But it was never a simple case of just well realised art direction and design, Ghost in the Shell’s foundation is much deeper and more complex, it’s worth contemplating then just what made the original film quite so good and just how bad this new version could be.

The first animated feature’s successes springboard from its iconic sci-fi imaginings and technological details but are rooted from a resonant philosophical and layered exploration of existence. Notions of identity, consciousness and the symbiotic correspondence and influence between biological and mechanised structures are soaked in the dialogue and narrative, Oshii purposely foregrounding these type of questions that would arise in a world where brains can be hacked and computers gain self awareness. Sure there’s criminal interrogation, detective work and the occasional exploding body part but the bent of the film rarely strays from its philosophical quandary. It’s as if the stunning animation and impeccable design are a robotic honey trap, singing you a beautiful rendition of a PHD thesis on Rene Descartes as you gormlessly lull towards existential kevlar rocks. The film pulls on these principle notions of what it means to be human by focussing on protagonist The Major’s personal investigation towards her self identity and whether she has a soul, or ‘ghost’, despite being a cyborg, an answer which is only ever suggested rather than directly stated. This idea of searching for the ’ghost’ also lend to both narrative drive in Section 9’s search for the criminal Puppetmaster, a criminal brain hacker, but also in our position as a viewer in relation to the point of emotional correspondence and engagement with The Major’s plight. We’re asked to really consider what it is The Major is thinking and feeling which is itself a point of emotional engagement which feels alarmingly alien at first.

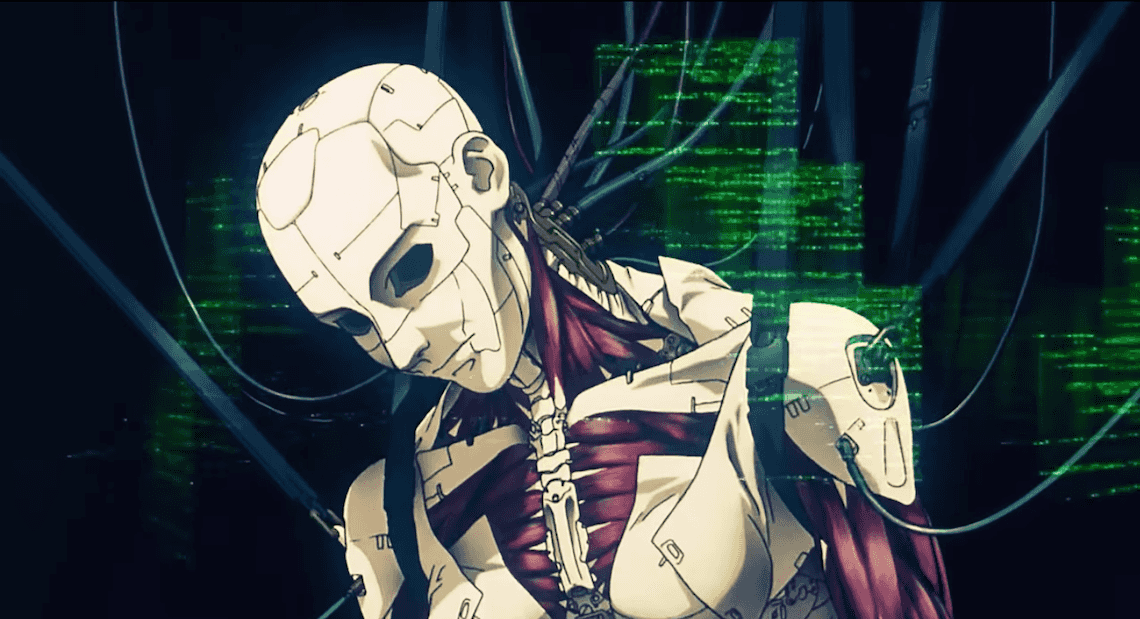

The tension that arises throughout The Major’s quest, one of inference when observed through an analysis of screen space, becomes a reflection of interconnectedness and disparity in the contemplation of whether she has a ‘ghost’. We often see characters framed by the gorgeous backdrops of the neo-Japan cityscape, dwarfed by the looming mass which itself appears almost as an organic life form, a knotted connector of busy byways, obelisk skyscrapers and densely jammed streets. This amplification of space is not just between the on screen characters but also between the viewer and the drama, the entangled city relegates intimacy and a consistent sensation of isolation simmers through the spectacle.These no doubt conscious choices are immersive in how they present and stimulate a sense of space between the audience and the film, which should make it groan like a 56k modem thrown into a vat of battery acid. But it quite beautifully does the opposite, heightening the central plight of The Major as well as drawing us into a very particular viewing platform. There’s an acknowledgment of the gap between us in these spatial choices, which allows for these ideas of the body/’ghost’ dichotomy to fold like an origami bird through the running time. Yet what stems from these choices is a paradox, offset and then crystallised: characters are hyper-connected via the technological advancement, jacking into the internet via sockets in their spines, yet personal identity is ever the more fragmented from this very practise. From ever greater interconnection the technological entwining changes our relationship to ourselves and each other, the spaces in which we occupy become part of an ever expanding cross weave of digital and physical space, occupied by flesh, wires and electricity.

Interconnection of the entire world lumbers an ever uncanny, if not more than a little uncomfortable parallel to our own, and with smart phones, tidal waves of wifi and the ‘internet of things’ already starting to smugly integrate into every facet of our existence, a world of hyper-connection is here in infancy. Ghost in the Shell posits ideas of our animal evolution as inextricably wed with the progression and advancement of the tools we have brought about to effect the world, the influence between them and how we have then operated in the world demonstrates a symbiotic progression that has, after time, led to technology merging with the human body. How the film tackles such incredibly difficult ideas in a consistently entertaining fashion, causes it to shimmer in the contemporary gaze a fresh now as it was in 1995.

And so these musings upon the multifaceted series lead to the forthcoming live action film, which despite the production so far appearing to commit to making the film look thoroughly handsome, along with appointing an interesting enough cast (Takeshi Kitano is always a safe bet and who doesn’t want to see Tricky in his thick Bristolian accent discussing cyborgs souls?) it still comes equipped with an undeniable sense of trepidation. After all the credentials of those producing, writing and directing are not quite the level of sagacious master-craftsmen some would no doubt wish to be at the helm of an opportunity such as this, it’s the scope that the world of Ghost in the Shell offers which makes for brow furrowing. The collated body of work which to draw upon is dense, the manga alone appearing as some neo-tome of cybernetic prophecy offering a vast array of narrative through-lines to infer and sculpt, whilst the frankly perverted levels of technical detailing are always at arms length to explode the vision. Granted this is a Hollywood adaptation with a no doubt hefty budget which will be aiming to fill up cinemas, but it cannot be buried that what’s truly on offer isn’t just the ability to render Scarlet Johansson fighting in nipple-less slow motion, but rather the chance to expand upon profound ideas through the particular power of the medium. It’s a new chapter in the series history, which offers a golden opportunity to reflect upon the contemporary world. Obviously there is no point in rallying like a puritanical fanboy before actually watching it as that’s painfully unintelligent, it can only be judged in due course, but the wake up call experienced at the screening made me realise how impressive Oshii’s vision was mesmerising, brain twisting and cutting edge at the time of release. Ghost in the Shell’s legacy is ever present and regardless of the success of this first live incarnation, the back catalogue and in particular the two animated films directed by Oshii will still remain as fascinating and important to the science fiction and animation canon as ever before. It’s something so laden with potential that even if the live action version is terrible I imagine it would barely put a dent in what’s come before.

‘Stand Alone Systems: The Ghost in The Shell’ is an article written by David Houston. You can follow David on Instagram or check his site on WordPress.