Rebirth born of division is a dangerous ideal if treated without due care and compassion. The signing of the Oberhausen Manifesto represented a rebirth of sorts, raising German cinema above simple propaganda toward widely held critical acclaim around the world. Whether or not it is useful to think in terms of visionaries and pioneers, every New Wave has them. In German New Cinema, we can throw perfunctory importance on the voices of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Wim Wenders and Werner Herzog. Perfunctory not because of any deficiency in these men’s respective visions or their right to be considered pioneers of the movement, but perfunctory because such auteur-ish definitions tends to push certain voices undeservingly to the fringes of the movement’s history. One thinks of a Margarethe Von Trotta here, or a Haro Senft, or, indeed, a Helma Sanders-Brahms or Helke Sander.

Many of these disremembered fringe voices, as is often the case in film or, indeed, general history, are female ones. Although, perhaps predictably, overlooked in the early scholarship regarding New German Cinema, female filmmakers were nonetheless an important part of it. Margarethe Von Trotta, in terms of said scholarship, is the most lasting of them, perhaps by virtue of her close association with Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Volker Schlondorff. Von Trotta collaborated with Schlondorff, who she was also married to between 1971 and 1991, on three films before going on to forge a solo-directorial career. Von Trotta wrote and acted in Schlondorff’s The Sudden Wealth of the Poor People of Komback (1971) before co-writing and co-directing The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum (1975) and writing, but not directing, Coup de Grace (1976). Von Trotta eventually broke out on her own with The Second Awakening of of Christa Klages ( 1978). It was, arguably, with her sisters trilogy where Von Trotta distilated her voice most clearly however. Of especial note in this regard was the second film in the trilogy, The German Sisters (1981)- also known under Die Bleierne Zeit and Juliane & Marianne. In it, Von Trotta excellently frames two divisive voices drawn from a similar ideology. Our titular characters are fighting for women’s rights, Juliane being a journalist and Marianne a terrorist. Marianne is jailed and Juliane feels obliged to support her in prison despite her vocal opposition to Marianne’s lifestyle. Von Trotta masterfully draws and intimate and highly engrossing portrait of division and familial duty and the follies inherent in both. Von Trotta, a master of dialogue and character development in her own right, raptly investigates state and personal histories which would become emblematic of the movement. Therein, she offers a rich and satisfying exploration of the roots of women’s rights and the place which its respective branches had in the culture of historical denial fundamental to her present-day Germany. Her frames are modest but arresting, her characters are revelatory and not a minute of her runtimes are wasted. Von Trotta is a master and her films should be remembered as such. Uniquelly, her cinematic voice is of as much value apart from as it is a part of the New Wave she helped create. She forged a filmic voice all her own whilst contributing to a wider conversation which would consume German cinema in the coming decades.

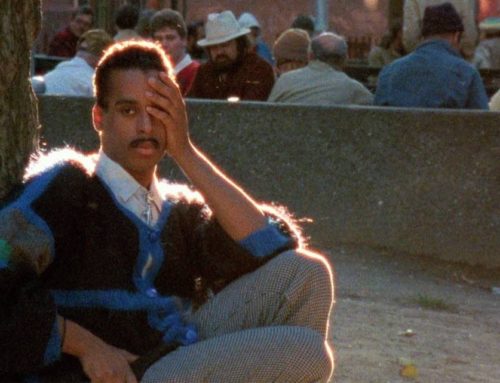

The de facto figurehead of the movement, Rainer Werner Fassbinder prolifically obsessed over stories of division and injustice in his short, explosive career. Producing some forty films before his untimely death at the age of 37 in 1982, Fassbinder mused over fascism, racism, classism and betrayal and our politicised instinct to turn a blind eye to them. Fassbinder arguably came to prominence following the popularity of Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974). The film tells the story of Emmi, an elderly, widowed cleaner, finding herself increasingly lonely in her old age, who looks to a fortysomething Moroccan Gastarbeiter, or ‘guest worker’, for romantic companionship. The two are met with ruinous opposition by the society around them and thus Fassbinder offers a stark warning toward the danger of Germany’s xenophobic past repeating itself. Considering it was shot in only 15 days, Fassbinder’s delicate and intricate framing is a revelation. His characters are statically contained in narrow frames, often doorways, windows or the tight spaces in-between, as stark, clashing block-colours fight for the viewer’s eye in what little unoccupied space remains. The whole thing creates an almost subliminal sense of divisionary dread and remains as brutally relevant today as it did upon its release. Indeed, history weaves patterns and xenophobia toward economic migrants is undeniably as deep a stitch as any. Emmi is by no means immune to unthinkingly succumbing to these patterns as she winsomely suggests the two dine in Hitler’s favourite restaurant and later casually denies Ali his request of couscous under the flimsy justification that he must adjust to German customs. Despite her apparent opposition to the communal aversion toward Ali for most of the film’s runtime, the story nonetheless culminates in Emmi snubbing another Gastarbeiter colleague, leaving her to eat lunch alone on the stairs in the manner to which Emmi herself was made accustom during her relationship with Ali. Thus, it would seem, Emmi has learned little of racial tolerance and the cycle perpetually continues. The film offers a continuation of the themes set forth in Katzelmacher (1969), where another economic migrant, played by Fassbinder himself, is met with vocal opposition by a group of aimless youths in a Munich apartment block. The youths, despite their apparent lack of ambition, feel a sense of ownership towards the economic engagement the immigrant Jorgos wishes to partake in. Similar xenophobic tendencies present themselves: anger over Jorgos’ limited German; an aversion towards his romantic engagement with a German woman and an assumption that he is a primitive, unwashed and sexually violent brute. Katzelmacher (1969) is a film, reminiscent of the French Nouvelle Vague, which is made up of short, repetitious frames as characters repeatedly tread familiar paths, both physically and orally. Fassbinder was intimately concerned with repeating patterns of hatred and division and the fact that he remains starkly relevant well over three decades after his death is testament to his prophetic prowess.

In the words of the Oberhausener Manifesto, ‘the decline of conventional German cinema has taken away the economic incentive that imposed a method that, to us, goes against the ideology of film’. The movement was a concerted effort to move away from conventional German cinema precisely by not allowing the country to forget its conventions. It painted a portrait of a politically turbulent time in German culture and politics which would be doomed to repeat itself, not just in the country, but the continent over. As achingly relevant as it ever was and only fleetingly examined here, New German Cinema is a wave worth getting lost in.

‘Papa’s Kino Ist Tot: Reflections on Divide and Loss by the German New Wave’ is an article written by Matthew Rooney.