I don’t know whether it’s because of my own queerness, my age (having been born in the early ‘90s to lefty parents), or something else entirely, but when I picture the 1980s and 1990s in my mind’s eye, the biggest associations that come to the fore are of conservative oppression, punk activism, and the AIDS epidemic. Life and death danced with one another, while oppression and expression played fisticuffs.

Of course, political oppression and the AIDS epidemic were entwined; leaders of the English-speaking world, i.e. Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, validated the villainization of AIDS sufferers, allowed the spread of disinformation, and allowed the deaths of tens of thousands of people (largely queer) before breaking silence. This silence, in terms of education, research, treatment, discussion, and simple recognition, allowed the epidemic to spread globally, and by 1999 over 14 million people had died from AIDS. It was within this silence that art, too, became woven into the fabric of this era. Moreover, while arts funding was being cut, the arts pushed forward in the spirit of resistance. For, in the times when art and expression are suppressed, they are often most needed. Art then becomes political and activistic in its existence.

I’ve gone a little broad-scope here; what I want to write about is the queer community of the late 1980s and early 1980s, and the emergence of what B. Ruby Rich termed New Queer Cinema. I have started a bit awry because the context in which this wave of cinema is born is so essential to its creation, its style, prominent filmmakers, reception, legacy, and of course its films’ content. As well as the resistance, suffering, and struggle in relation to the AIDS epidemic, the New Queer Cinema was also largely due to the influence of the academic development of Queer Theory in the 1980s. As a continuation from Feminist Theory, Queer Theory aimed to further push debates in gender and sexuality, identifying that notions of gender and sexuality were social constructs, and deconstructing hetero-patriarchal norms and imposed binaries. As such, the term ‘Queer’ started being used as an umbrella terms for any LGBTQI+ identity, recognising the fluidity of sexuality.

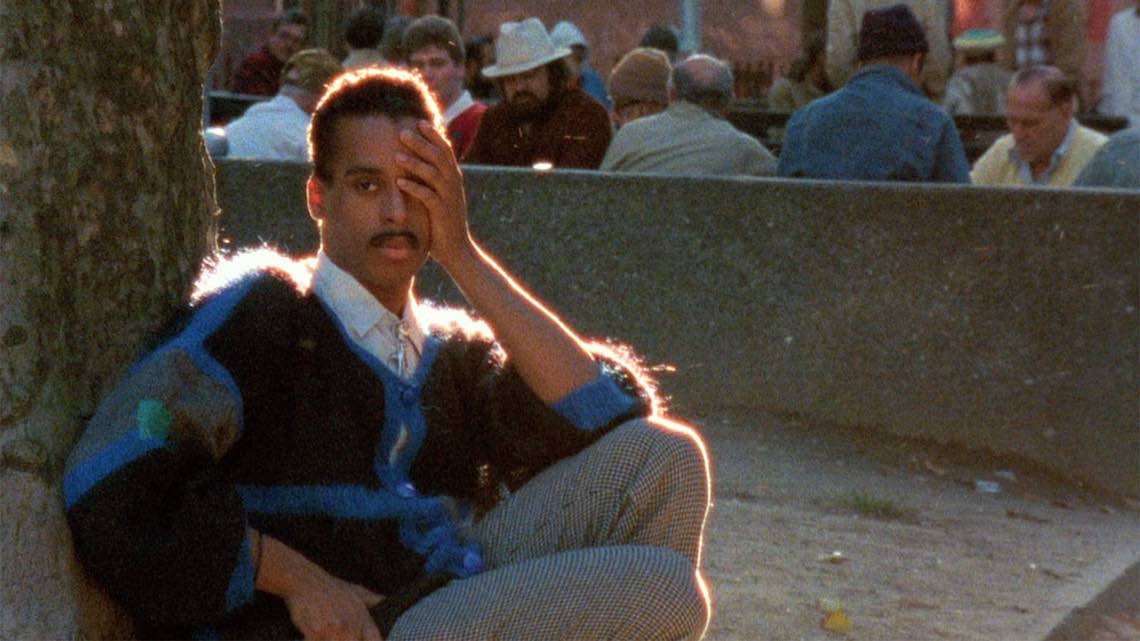

In terms of cinema, the 1980s also saw a great proliferation of identity-based film festivals, that popped up in response to needs for expression, network formation, and active discussion. It’s not really a surprise then, with all of this going on at once, that when film critic and scholar B. Ruby Rich did a lap of the international film festival circuit in 1992, she proclaimed that “1992 has become a watershed year of independent gay and lesbian film and video”. The festival boom (relatively speaking) of queer film led to buzz, mainstream press, distribution and exhibition of queer films, and there was a feeling like the door had been swung open.

Reading B. Ruby Rich’s Sight & Sound article now, there is sure enough a consistency in style, aesthetic, content, and story – at least in the films that I recognise – i.e. the films that achieved funding, distribution and legacy. The most ‘famous’ films of the NQC like Todd Haynes’ Poison, Derek Jarman’s Edward II and Tom Kalin’s Swoon each follow what has become deemed conventional of the NQC. By this I mean the ways in which they play with and rework history, their experimental form: rich and defiant, their wit, and also their positioning of protagonists as outsiders and renegades.

While this is the general perception of New Queer Cinema, and while the aforementioned films are masterpieces, each wonderful and important and beautiful, there is a lot to NQC that has been forgotten, or was never encouraged to prosper. As a queer woman, B. Ruby Rich is clear in highlighting the discrepancies in representation and success of queer films. She writes that unsurprisingly, the ‘prominent’ films – films with the bigger budgets, and the bigger buzz – are largely made by white men. Meanwhile, women and people of colour are side-lined. Rich gives a lot of attention to the innovative and modern, yet ignored videos generated by lesbians – “Surprise, the amazing new lesbian videos that are redefining the whole dyke relationship to popular culture remains hard to find”. What I’m trying to say is that there are a lot of stories within the NQC movement that struggled to get an ear or a pair of eyes, and certainly struggled to be put in the archive for preservation, celebration, and a place in cinematic history. I’m thinking of filmmakers like Cheryl Dunye (The Watermelon Woman, She Don’t Fade, Vanilla Sex), Sadie Benning (Jollies), Cecilia Barriga (The Meeting of Two Queens), Cleo Uebelmann (Mano Destra), and Isaac Julien (Young Rebel Souls), but do have a read of Rich’s 1992 article to get a fuller idea of what is out there.

That being said, Jennie Livingston’s film Paris is Burning was also produced in this circuit, released in 1991. The film is not mentioned too much by Rich, in fact I was a bit disappointed that she doesn’t mention trans cinema or lack thereof, as part of her general recognition that inclusion and equality was lacking. It’s really interesting then, that Paris is Burning has become perhaps one of the best known and loved films of NQC in a mainstream landscape (it is currently streaming on Netflix and I don’t think I can say that for many or perhaps any of the NQC films that Rich speaks of). There are some issues with Paris, mainly in that Livingstone allegedly did not give any earnings to the participants of the film. This is obviously hugely problematic, when on and off screen trans representation is so scarce, and when trans communities (particularly black trans communities) suffer massively disproportionate levels of socio-economic disadvantage. However, Paris is the first film that represented black trans experience, and it is hugely educational for the wider world. It’s had endless rippling effects all the way up to contemporary popular culture, and is generally beloved by the queer community.

It is also worth noting that while the male filmmakers dominated the NQC of the 1990s, there were a handful of massively facilitating and sort of king-making queer women behind the scenes. One such is of course B. Ruby Rich, whose criticism remains iconic, and who also funded several queer filmmakers. There is also Christine Vachon, legendary producer who worked on the likes of Swoon, Poison (Vachon remains Haynes’ long-time collaborator), Boys Don’t Cry (dir. Kimberly Peirce, 1999), and the slightly later queer classic, Hedwig and the Angry Inch (dir. John Cameron Mitchell, 2001).

It is wholly understandable that the male-made NQC films received deserved attention and acclaim because they were a direct product of the climate, and provided a mouthpiece for an otherwise silenced community that was essentially being allowed to self-combust. Simultaneously, however, it should not be the case that a single segment of the queer community is seen whilst the rest remains invisible, un recognised and not remembered. Whilst we learn of the dominant voices of the wave, let’s also dig a little deeper, to the women, the lesbians, the people of colour, the trans folk, and everybody queer, whose histories (both cinematic and otherwise) must be neither ignored nor erased.

‘New Queer Cinema – A contemporary glance back at the urgent wave’ is an article written by Kate Fahi. You can follow Kate’s work on Instagram.