Until very recently, Hollywood’s Asian characters were pretty much limited to the odd doctor here or there, the ‘dragon lady’ love interest, beggars on the streets of South Asia, or, let’s not forget the holy grail: the ‘New York taxi driver with the most overly-exaggerated Indian accent you’ll ever hear’. But that slowly started to change – now more than ever, Hollywood and worldwide audiences alike are welcoming Asian-led content to their screens. Even where Asian actors aren’t leading the stories, Hollywood is gradually giving more space to Asian directors. 2020 was a landmark year for this, with Japanese-Australian director Natalie Erika James’ moving horror Relic, Cathy Yan’s ultra-fun Birds of Prey and my personal favourite 2020 release; Chloé Zhao’s breath taking Nomadland. We’re even seeing a rise in South Asian actors taking over the big screen – with Dev Patel and Riz Ahmed becoming household names (and I’m sure casting agents will one day realise that Mindy Kaling is not the only South Asian actress available for Hollywood roles). And so began Hollywood’s RenAsiassance.

One of the biggest Asian-led box office hits of recent years was 2018’s Crazy Rich Asians. Lauded by both critics and audiences, Crazy Rich Asians gave us the fun, extravagant rom-com with an all-Asian cast that we needed. But it also added to the ultimately taking-a-step-in-the-wrong-direction stereotype of hyper-wealth being prominent in general Asian lifestyle, a trope that we see too often on screen (further exemplified by Netflix’s recent Bling Empire series).

Contrastingly, 2018’s Searching and 2019’s The Farewell also welcomed critical acclaim, and featured career-defining performances from John Cho and Awkwafina respectively. Lulu Wang’s delicate direction of The Farewell especially has made her one to watch. Both stories were unique in portraying grief beautifully, and more importantly, gave us more ‘normal’ stories of Asian life.

Then, in 2019, came the film that shook the world: Parasite. Bong Joon-ho’s explosive Korean social satire not only made history by becoming the first foreign-language Best Picture winner (aka the only good moment of 2020), it also encouraged a whole new audience to tolerate subtitles and take a chance on foreign film. Parasite’s wild and well-earned success can in part be explained by its dramatized yet realistic depiction of universal class struggle and frustration. It is just one of many examples of how Asian directors and writers are capable of crafting internationally relevant and important stories, and how these are the right voices to bring to the forefront.

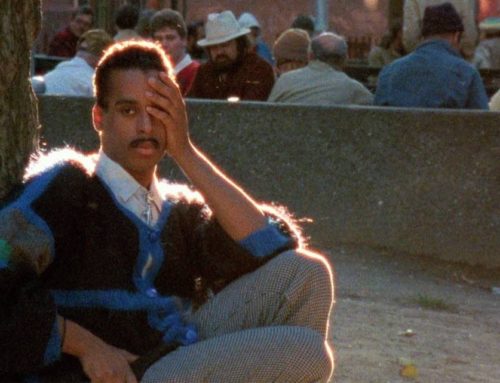

Most recently, in late 2020, came Lee Isaac Chung’s Minari: a film so beautiful yet heart-achingly ‘real’ that I found it hard to think about anything else for weeks after my first viewing. In the stunning tale of a Korean family’s quest for a better life in rural Arkansas, Steven Yeun exquisitely plays Jacob, who dreams of running a successful farm alongside his wife Monica (Han Ye-ri), his daughter Anne (Noel Cho) and his son David (Alan Kim). Minari is a shining example of the kind of stories we need to see in Hollywood’s rising RenAsiassance – the stories of real families and real transatlantic hopes and dreams that can resonate with, well, anybody.

Immediately within the first few minutes of the film, it’s easy to fall in love with our protagonists and their American dream; made even easier by Emile Mosseri’s dreamy and tender score. There is a line said by Monica to Jacob early on in the film which shapes the essence of the story entirely: “This land is your dream?” In only five words, this line encapsulates the unrealistic belief bestowed upon immigrants that everything will magically be better once you leave your homeland for the ‘promised land’.

As an immigrant myself, this is the first immigrant tale I’ve seen that so accurately depicts the harmful expectations Asians grow up with, and how this only gets worse in an unfamiliar setting. From the favouritism of Asian sons, portrayed perfectly by David’s grandma (played thoughtfully by Youn Yuh-jung) only wanting the best for him while pushing his sister into the shadows; to showing how this transcends into the pressure placed on Asian men to be bread-winning patriarchs who constantly need to ‘provide’, again captured in a single line by Jacob in the peak of his frustration: “I just want them to see me succeed in something for once”. In the most striking child performance since Brooklynn Prince’s Moonee in The Florida Project (2017), Alan Kim’s seamless portrayal of David’s development from the all-too-real shunning of pretty much anything to do with their homeland done by immigrant kids (complaining about his grandmother’s ‘Korea smell’) to his gradual unconditional respect for his grandmother is one of the most moving character arcs I’ve ever seen.

Another of Minari’s many triumphs is how it shies away from the age-old trope of white southern Americans being scary unwelcoming racists to the new foreigners. We all know that kind of hostility unfortunately does exist, but why should we constantly have to be exposed to racial divide trauma on screen within POC-led narratives? What Chung depicts so beautifully in David and Anne’s relationships with their fellow white church-goers is how well-meaning child-like ignorance can blossom into genuinely meaningful relationships, without forced assimilation, that grow to celebrate ‘foreign’ cultures.

The sheer beauty of Minari lies in its simplicity. With credit to Lachlan Milne’s stellar cinematography, the sun-soaked frames of the family frolicking about in the lush greens of their new land; marking it as their own, carry the same poetic realism of Satyajit Ray’s Apu trilogy and François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959). It is, overall, a simple story of modern family life that ultimately does not sugar-coat the heartbreak of when things don’t work out in the promised land. What Chung has captured so poignantly is that, along with carrying relics like the Minari plant from their home countries to their new land, immigrants also carry generational trauma, an overarching determination to succeed, and an unbreakable hope for a brighter future. But, just like the Minari plant; loving, nurturing relationships strong enough to survive any hardship can thrive anywhere in the world – with the necessary unwavering patience, care and resilience.

‘Minari and the Rising Legacy of Hollywood’s RenAsiassance’ is an article written by Ruwaida Khandker. You can follow Ruwaida on Instagram.