I was watching the BBC’s His Dark Materials (2019) and whilst I mostly enjoyed the story, acting and other aspects of the drama, one question kept coming up; where are the characters’ dæmons?

For those unaware of the YA book series by Philip Pullman, the Northern Lights (1995), which the majority of the first series of His Dark Materials is based on, is set in an alternative universe in which all humans are accompanied by their dæmon – their soul external to their body that takes the form of an animal. Yet the TV series appears to put less stress on this part of the source, crowds of background characters swarm the series without an animal in sight. It seems that only the major characters warrant a visible dæmon. I know this may seem like a trivial point but the relationship between a person and their dæmon is crucial to the story, one that is blindsided by the BBC adaptation. Of course I don’t imagine that this was intentional on part of the filmmakers – the issue is of CGI and budget. This in turn is an overall issue in British mainstream animation. CGI is expensive and all the dæmons are CGI. The BBC simply couldn’t afford to animate all the multitude of creatures that would need to appear to accurately replicate the book.

Fair enough, I suppose?

Well, I watched a behind-the-scenes video of His Dark Materials on how the dæmons were originally simple puppets that actors would interact with. The puppets were then animated over by CGI in post-production. This made me wonder – could the dæmon-puppets not remain puppets (albeit more complex) in the finished product? Puppet animation is by no means less intricate but it is, in general terms, less expensive than CGI. I imagined what possibilities this could unleash for the series, something akin to the dark atmosphere and haunting beauty of Jim Henson’s The Storyteller (1987).

Saying this I do not disprove of CGI, all animation mediums have their merits. Many puppet and stop-motion animated films incorporate CGI to enhance the image. It is just that puppet and stop-motion animation in recent years has been ignored by British productions in favour of sub-par CGI. We can look at recent fare such as the BBC’s Watership Down (2018), Andy Serkis’s Mowgli: Legend of the Jungle (2018) or Moominvalley (2019) as evidence for this attempt to mimic big budget American animation. Britain has had a long-standing tradition in both puppet and stop-motion animation. Many of us might think of the vintage twee of Oliver Postgate and Peter Firmin, or the more recent Aardman films. Henson’s The Muppets Show (1976 – 1982) was filmed and co-produced in the UK, as well as his later projects The Dark Crystal (1982), Labyrinth (1986) and The Storyteller. The appeal of this physical medium could be put down to its emphasis on touch and texture. In The Art of Stop-Motion Animation (2006) animator Ken Priebe states that this animation is linked to the ‘…subconscious mind, in that we all have memories of playing with dolls, action figures or Play-Doh from our childhood, and the tactile senses that come with it…’ and to see characters move on screen ‘…harkens us back to old pastimes and imagining the life we would give to our toys.’ Whilst Priebe was discussing this effect in regard to stop-motion, the same can be argued when audiences watch puppet animation. Both are involved in the material – the characters exist in our world and can be physically experienced, which characters created via software cannot.

On the other hand, despite this charm that enthusiasts like Priebe describe, Aardman never supersedes the box office draw of its American CGI competitors. The most recent examples include A Shaun the Sheep Movie: Farmageddon (2019) that has grossed approximately $30 million, whereas the Disney sequel Frozen 2 (2019) has grossed approximately over $900 million. It would seem audiences prefer CGI – maybe there is an assumption that Frozen 2 will provide more spectacle and therefore more value for money. Since we seem to be witnessing the decline of the mid-budget movie which Aardman films commonly are, this could well be true. Surely we can then understand British producers nervousness about returning to these practical animation methods of yesteryear.

To examine these points regarding box office we would expect puppetry and stop-motion to be a dying format. Though by seeing the cult following of The Dark Crystal and its television reboot Age of Resistance (2019), as well as the international affection for Aardman’s own Wallace and Gromit, this is far from the case. Perhaps wider audiences should be more willing to risk their money buying a ticket to see a puppet or stop-motion film rather than a CGI one, and likewise producers should be more willing to experiment with physical forms of animation. There is no lack of talent in this field – I recommend watching the Animation 2018 series available for free on the BFI player to see some innovative works by young animators. Trying to be like every other major film or television programme isn’t going to leave an impression on viewers in the long term. The current hit of the puppet character ‘Baby Yoda’ has even overshadowed its originating web series The Mandalorian (2019). The alien puppet was due to be replaced with CGI in post-production in the same way the dæmons in His Dark Materials were, if it weren’t for the objection of Werner Herzog. Herzog’s intervention led to the creature becoming a viral phenomenon and a demand for Baby Yoda-based merchandise from fans.

What has caused the runaway stardom of this character?

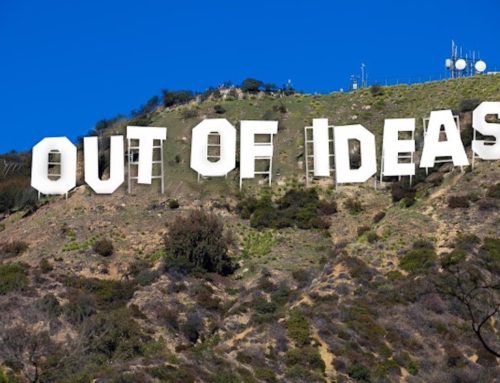

On discussing the creature, Zach Vasquez of the Guardian reiterates previous reasons for puppetry’s draw, stating that it is ‘…the tactile – and at times uncanny – nature of the thing that is responsible for people’s visceral reaction to it…’ The same can be true of Henson, Aardman and the countless other artists who have worked in this form. Future puppet and stop-motion projects can prosper if producers are willing to experiment and create media that use these physical methods. Audiences react to techniques that break the mould and can even prove successful because of its unique style. Whilst it is too late for projects like Watership Down and His Dark Materials, I nevertheless ask why settle for poor CGI that risks alienating audiences and critics – and proving in some respects detrimental to the story – when you can have quality puppet or stop-motion for nearly the same price. British animation has been notoriously lacking in the monetary department but has nonetheless created quality content. There’s no point in attempting to imitate the likes of Disney or Pixar – aspire to be exceptional. Who cares if you’ve got no budget – why not embrace it?

‘Losing Touch: Why diminishing the use of stop-motion and puppetry in British animation is a misstep’ is an article written by Jacob George Goodwin.