In a Lisbon slum a woman arrives to mourn the death of her long absent husband. By day she gradually attempts to fix his dilapidated home but by night she struggles to come to terms with his sudden disappearance while they lived in the Portuguese colony back in Cape Verde. Things are in stasis: people walk slowly, churches are empty, streets are bare, and little actually happens. The most considerable action takes the form of long, static monologues that illuminate the woman’s past and her reasons for arriving in Lisbon. The film, Pedro Costa’s latest, Vitalina Varela (2020), uses non-professional actors and couples this with minimal conversations and dialogue. Shot almost entirely at night, the film uses minimal light sources (though the use of lighting here has a very stark and haunting impact). Its stylistic application is reminiscent of Ingmar Bergman’s contemplative work in the 50s and 60s – for example, the chiaroscuro cinematography combined with Max von Sydow’s existential reflections while talking to Death in The Seventh Seal (1957). Bergman’s renowned filmic style – akin with other progenitors of the time like Michaelangelo Antonioni, the Italian Neorealist movement, Andrei Tarkovsky, Béla Tarr, Chantal Akerman, and Theo Angelopoulos to name a small few – can be seen stamped, like in Costa’s film, across contemporary cinema. Hence, laying the foundations for what can be considered ‘Slow Cinema’ or ‘contemporary contemplative cinema’, whose fundamental properties rely on the use of the long take, undramatic narrativisation, an audio-visual depiction of mundanity and everydayness, and the awareness of duration or the unfolding of time.

Pedro Costa’s film (along with others he has made throughout his career) particularly focuses this style on barren spaces – be it a bare street or an empty room. He uses his stark lighting to fill the space with either light or darkness, visually placing his characters into spaces of isolation. Though, in a form that is borne from a recording of images that move and in an age of a popular cinema that relishes pace and action, it might be odd to focus on something as antithetical to cinema as emptiness can seem to be. Clearing a frame of activity, focusing on minimal movement, or highlighting blank space at first glance can be viewed as misusing cinema’s many beautiful characteristics. But Pedro Costa’s style – along with the other directors recurrently associated with the cinema of slowness – interrogates the treatment of space and use space as a visual signifier that either drives narrative or manifests the interior landscape of its characters.

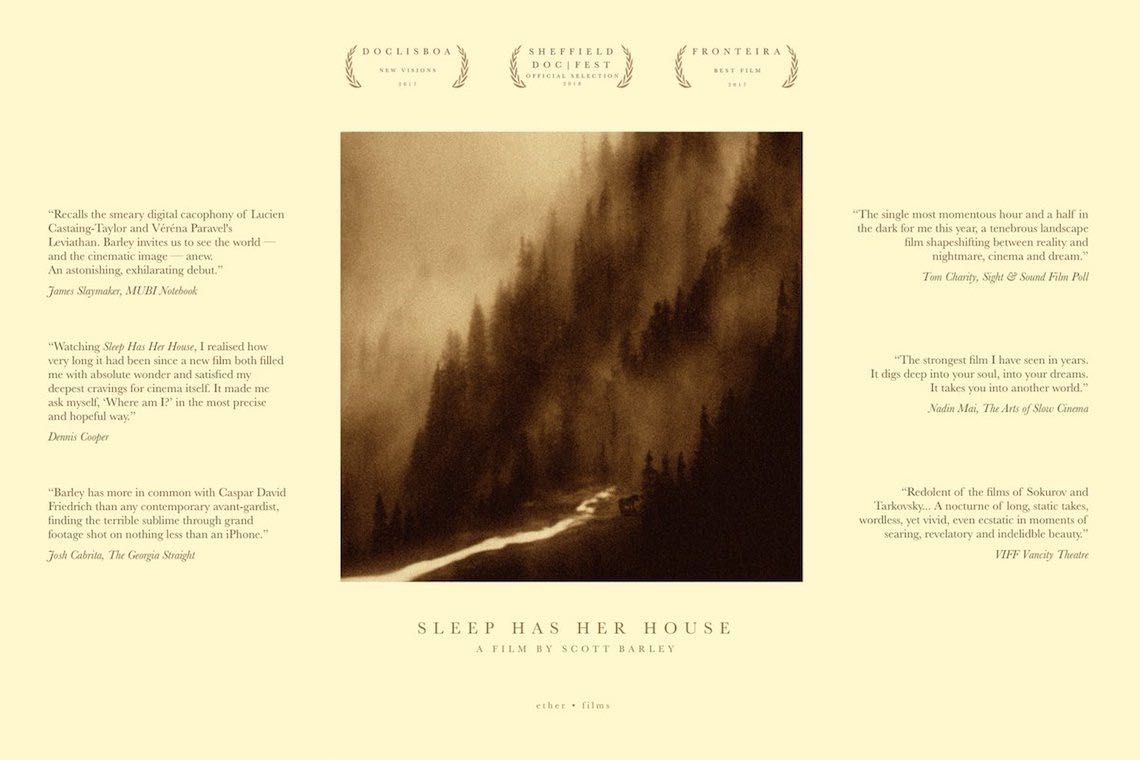

All these characteristics outline the visual mode of storytelling most fundamental to the cinema of slowness and are particularly noticeable in the films of contemporary art filmmaker, Scott Barley. Where Pedro Costa, in Vitalina Varela, focuses his lens on people and employs slowness – the static, long take, mundane actions, bare locations – based around the lead Varela character’s disconnection and isolation, Scott Barley, particularly in his most recent feature film Sleep Has Her House (2017), points his focus towards external landscapes.

Sleep Has Her House, filmed on an iPhone in 2015 and 2016, is an elemental, harshly sensory visual story of an ethereal presence that passes through vast, barren landscapes. This dark presence – that moves as the mist moves or screams like the thunder – leaves a mysterious death in its wake, leaving the settings void of human activity. The landscapes, on their path to apocalypse, drift in and out of a misty darkness and a hazy cloudiness; very little sunlight reaches the undergrowth, trees, and rivers of this unknown scenery that is only sparsely populated by animals. There is something mythical in the images as their vast grandeur is laid bare; the extreme distance of which the camera records from absorbs the magnitude and beauty of the hills, forests, or lakes.

Barley, here, returns to the basics of cinema, owing a debt to the ‘cinema of attractions’ seen during cinema’s infancy when the Lumière brothers, among others, filmed mundane events in brief, single tableau. This form of early cinema relied on the single take and thus recorded the frontality of documentary-like events. Scott Barley, too, chooses to rely on a frontal view, eschewing lateral movement by primarily keeping his shots very still. By doing so, the sight of a waterfall flowing into a river or clouds drifting in a sepia sky gain greater importance beyond their authenticity. As the camera remains static, apart from an occasional slow zoom, the wind or water moves within the frame thus stressing the images disjuncture with its audience: we are still, the image is not. Crucially, Barley also prolongs these images by use of the long take; the longest shot recorded in the film plays for a staggering 11 minutes while the other shots are of equal scale. Extending the duration of these shots, perhaps beyond what many viewers would be familiar to, ultimately draws particular attention to the shot’s temporality.

Crucially, though, Sleep Has Her House empties its landscapes to create absent, vast spaces. In relation to this, Scott Barley, at the Slow Film Festival in Mayfield, East Sussex, said “I think slow cinema has this magical way of being a conduit of achieving something that brings us closer to our bodies” (interview can be read in full via the Moving Image Artists Film Journal here). Barley’s depiction of the Sublime – large, cascading hillsides or the almost cosmic, sunburnt rivers – dwarfs the everyday and the human hereby balancing the real with the unreal. Thus, this emptiness becomes visually and aurally penetrative whereby Barley relies on the spectacle of image and a searing soundscape to be the film’s narrative drive. Barley pertinently continues by saying “we are grappling with this folly of trying to supersede nature” and he has often interrogated a connection between nature and the body in his short-form work too. In his film Hunter (2015), for example, a pale hand stretches from behind the camera and wades through a blackness and is left aimless and lost. Outstretched and wanting to touch the distant skyline, the hand never truly connects; lit by a bright light too, the hand in the foreground seems fully detached from the black of the landscape beyond it. While Sleep Has Her House never explicitly draws a connection to bodies on this kind of scale, Barley’s use of Sublime imagery and the shots prolonged duration draw the audience member closer into a contemplative state of viewing.

Going back to the monologue sequences in Vitalina Varela, they are primarily shot using a close-up. By doing so, Costa once again draws us closer to Varela’s mentality whereby the contours and crevices of her face are placed centre stage. But Barley rarely uses the close-up, instead choosing to shoot in extreme wide shots or shots that illuminate the landscape as a whole. Thus, Barley is explicitly detaching the audience’s engagement on an emotional level and moves towards a contemplative relationship with the images. Much like a J.M.W Turner painting, Barley uses extreme wide angles to measure the mood of nature by which water, land, and sky are combined to make painterly portraits of the natural world. That said, Sleep Has Her House opens in extreme close-up on a waterfall though Barley’s use of the close-up, here, over magnifies and distorts the image which draws us closer on a more abstract level. Thus, even in close-up things seem larger than usual. All this, alongside the long take and the use of vast expanses, adhere to a cinema of slowness but Barley astutely employs this style in his own unique and contemporary way.

Evidently, then, there are similarities across many contemporary films that can be bracketed in this movement of slow cinema; namely a use of long takes that are coupled with absent and empty mise-en-scène. Slow cinema thus takes a unique place in the landscape of filmmaking. Tiago De Luca explains, in his introduction to the book, Slow Cinema, that it “could be best interpreted as a reaction against the increasing speed of mainstream movies” and that slowness is necessary as an antidote to the ubiquitous speed of modern living. Barley’s singular iPhone photography of the British countryside, then, is just another indication of his incessant interest with corporeality and he grapples with a detachment of popularised cinema. As a result, his films are both beautiful and haunting, scary yet calming and by being so he magically allows for an audience to participate in the viewing process on an intellectual basis.

‘Emptying Space: Contemporary Slow Cinema and the Work of Scott Barley’ is an article written by Edwin Miles. You can follow Edwin on Twitter and Instagram.